One of the hidden protagonists of the Old Testament is Wine.

Its frequent presence, however, is not always marked by the same tones: running trough the pages with an eye to the many episodes in which wine and the vineyard are involved, we can see that among the ancient Hebrew people these elements, so familiar to us today, were considered alternatively as the symbol of evil or good. Examining the question more closely, we discover that this attitude, as drastic in the positive as in the negative, is dictated not by rational motivation but by strictly political convenience.

Wine is the “demon” when the Hebrew people is at war, when it is in search of a new land, when it is suffering the tyranny of another people and sees no prospect other than emigration and fight.

Wine is a good and sanctifying element when the nation is at peace, the land where they live is secure, the efforts of all are directed to the construction of the large and small works of civilization.

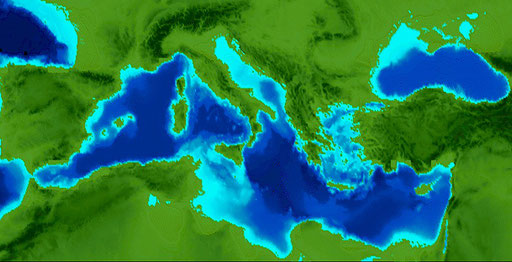

The decision to plant a vineyard, perhaps more then than now, meant living in the certainty of ownership, sure of being able to invest the long years necessary to enjoy the first harvest, able to count on a favorable and social atmosphere, capable of disinterested help in moments of difficulty. It is not by chance that the history of wine is parallel to, and an integral part of, that of the great civilizations and that its flowering takes place in the incomparable setting of the land touched by the Mediterranean.

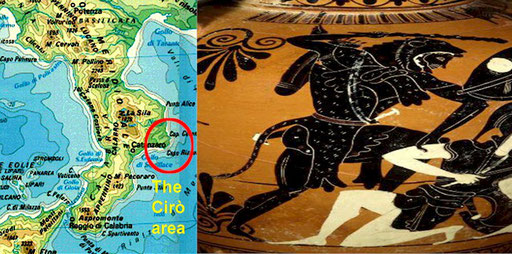

We owe to the Greek civilization the first great expressions of oenological techniques, the first wines constant enough in quality to take their place, by right, as protagonists of immortal works, in poetry, painting and sculpture.

And we owe to the Greeks the importation, on our southern shores, of an advanced practice of cultivation which allowed the wines of Magna Grecia to become as famous and as widely appreciated as the architectonic, intellectual, and social works which were realized in Syracuse, Agrigentum, Paestum, Selinunte, Sibari, and Metaponto.

The Greeks brought to Italy first the wines, setting up a profitable trade; then the vines that they had diligently refined during centuries of agricultural practice; and finally the techniques of cultivation and winemaking: a priceless heritage on which, with almost no variation, a large part of fortunes of the Roman winemaking world was based.

It was a slow start, and although the qualities of good wine were appreciated as much in the clamor of the taverns as in the harmony of the most refined verses, for centuries the law tried to limit its use, forbidding it to young until the age of 21, forcing Romulus himself to use milk as a sacrificial beverage, leading King Numa to forbid its sprinkling on the pyre, levying heavy penalties on the women who may use of it.

These were the limitations of a state that was slowly constructing its own civilization and, at the same time, its own oenology.

Wines arrived in Rome, however, first of all from Magna Grecia, and there was a good market of Mamertino, still produced today in the province of Messina, rich in sun and alcoholic content, comparable, if we skip over more than twenty centuries, to the driest White Port; or Pollio, this too still vital in the province of Syracuse, sweet and strong, from slightly wilted muscat grapes; and Tauromenitanum, from the coastal hills of Taormina, lost to us today.

The most celebrated wine, however, was produced on the doorstep, at Mondragone and nearby, an its name, Falernum, even today evokes the most beautiful images that can be associated with a Wine. Sung by all the greatest poets, it an boast quotations from Catullus, Martial, Pliny and then, litte by little, right up to Torquato Tasso and Giosuè Carducci.

The Romans were so expert and so exacting that they distinguished, in the production of this wine, the best zone (the "cru"), preferring those originating from the vineyards of the lower slopes, and distinguishing moreover between Gaurano, produced on the slopes of Monte Gauro, and Faustiano.

Along with Falerno were Cecubo, with its bright ruby color, still produced in Fondi, Sperlonga and Gaeta; Velletrano, similar to our contemporary Velletri; and Setino of Sezze. From more distant lands, Peligno and Petruziano, forefathers of the modern Montepulciano and Cerasuolo d'Abbruzzo; and from the Veneto the historical fathers of Prosecco, Preciano, and Reatico.

Wine trade in Rome became, in the courses of decades, so intense that the State felt the necessity of regulating it in great detail, and even of assigning it an entire specialized market, the Horrea Galbae, the largest of all the city markets, spread over an area of about eight acres. It gathered all those involved in the wine trade in a corporation, the Corpus Vinariorum, considered one of the six most powerful of the city.

For several centuries the strength of the wine trade was to be found in the Greek wines, in particular those from the island of Rhodes, Cyprus, Lesbos, and Chios. As time went on, these gave ground to those from Spain, Asia Minor and North Africa.

Step by step the new Italian wines began to appear on the Roman market, descendants of those pioneers which ever since the Fifth Century B.C. caused Sophocles to say that Italy was the land preferred by Bacchus and led writers and historians to call it Enotria, land of wine and vineyards.

To search for a rational thread to led us in the discovery of Italian wines from the Roman Empire to today would be a sterile boring undertaking. Better to trust ourselves to the light and joyous guide of poetic verse and literary page to illuminate us, if what we seek is the witness of the untamable concentration of vitality contained in a glass of wine.

THE POETS

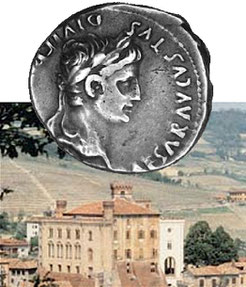

Thus, it cannot be by chance that Virgil, Pliny, Horace, Strabone, and Augustus spent the time to sing the praises of the "Retic wines", coming from "Rezia" which we identify today as the Valtellina, a harsh land even now difficult to cultivate, yet still worthy of the praise of our poets.

From another land on the northern border of the peninsula, the Val d'Aosta, comes evidence of a wine which made itself appreciated for its quality at imperial banquets, the Vien de Nus, a ruby red whose flavor seems to have struck

Pontius Pilate, passing through the area, enough to make him its

determined patron in the best Roman society.

THE KNIGHTS

Incredibly, wine manages to unite, as actors on the same stage, poets and politicians, historians and glorious leaders.

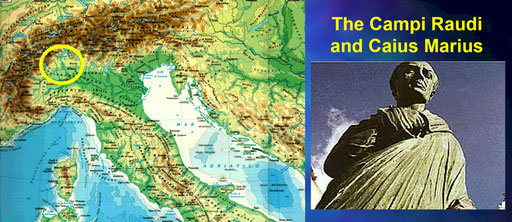

Often it is their companion in triumph, sometimes a secret and insidious accomplice as in the case of the Bianco dei Campi Raudi, a golden wine still produced in the province of Novara. In 101 B.C. it became a surprising ally of Caius Marius, having led the tribes of the Cimbri to the ease of a stable life.

Right in the Plains of the Campi Raudi was the bloody battle which managed to stop the first barbarian invasion of the peninsula: 120.000 dead and wounded, 60.000 prisoners; historians who elaborate the virtues of the Roman legionaries; popular tradition which identifies the historical battle in the name of the wine, the only survivor, two millennia later.

If a wine helped the Romans defeat the first barbarian invader, another unfortunately gave the enemy the strength and vigor to get the best of the legions and to put Rome in the sack. It is 410 A.D. , and Alaric, King of the Visigoths, comes down from Veneto with his hordes.

Going through the territory of the Marche, he encounters the wines produced around Cupramontana, and “considering that nothing brings health and warlike vigor better than Verdicchio”, he decided to requisition no less than forty loads.

What happened to Rome upon Alaric’s arrival is well known, even it is not all the fault of the Verdicchio, more suited in its gentleness to accompany thoughts of peace, of joy, and peraphs of amorous struggle.

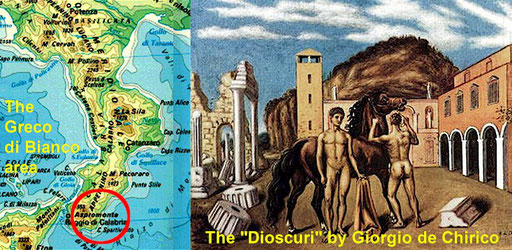

And yet, tales of wine as the carrier of warlike energy recur in every historical epoch and enclose in myth even the most ancient of Italian wines, that Greco di Bianco produced in a few well-defined vineyards of the town of Bianco (defined over 2,000 years ago, beyond any intervention of law), in the province of Reggio Calabria.

Here history tells us that in 560 B.C. 10,000 Locresi, encouraged and invigorated by abundant libations of Greco, managed to defeat the army of Crotone, composed of 130,000 men. In the sequences of the bloody battle, as if to tone down the merits attributed to that wine, myth comes into play, on the side of Locri, with Castor and Pollux sent to their aid by Apollo; but we, rational inhabitants of the XXI century, must note that that Greco di Bianco, dense sweet, and rich with thousand flavors and perfumes, is still there for all those who can appreciate it, while all traces of the Dioscuri disappeared some time ago.

If wars fill history, sometimes history gives way to harsh battles. This is the case of the Natural History of Pliny, who is known also for the arguments unleashed among his remote descendants. In one passage he cites the Pucinum, a wine of the upper Adriatic which some identify today as the Prosecco of Trieste, harshly contradicted by those who consider it the father of Refosco.

Whichever it was (but the definition of the wine of Pucinum as "omnium nigerrima" makes us lean toward the second choice), the annals record it as the wine preferred by Livia, his wife, a shrewd and eager connisseur who, skilled in the administration of her gastronomic desires, managed to live to the age of 86, a real record for those times.

THE WOMEN

With Livia we have had our first encounter with a woman in the world of wine. Previously it was just a flight of vestals, of damsels, of priestesses, of extras pleasing to the sight but unused in the context, except for the suggestion of a removal, with the complicity of intoxication, to the practice of other kinds of pleasures.

The memory of Galla Placida will follow that of Livia: that Byzantine empress who, delighted by a cup of Albana, exclaimed, "Thou art too good, oh golden wine, to be drunk from a rustic cup. Would I could drink thee in gold!" And the exclamation was sufficient to baptize the village where the episode took place "Bertinoro", which is still the unrivalled capital of Albana of Romagna.

It is a fragile legend, easy to dispute (what language did they speak, in the 5th Century A.D., in the Byzantine court?), but it is witness to the vocation of this wine, worthy since its origins of the imperial table and later of that of Frederick Barbarossa, still imperial but decidedly less refined, greedy to the point of getting drunk on it every day.

The quicksands of classical times could hold us down for pages and pages of discourse on wines and republican, imperial and late imperial quotations, but before we take the decisive leap forward which will allow us to skip among the hundred wines which alternate on our tables today, we must above all make note of Cirò, in ancient times "Cremissa", a warm and generous Calabrian wine, today more than ever the undisputed symbol of high-quality Southern wines.

Such was its reputation that it was given to the athletes returning victorious from the Olympics; and in spite of all the great wines - Italian, French, and German - that have reached fame trough the centuries, during the Olympic Games at Mexico City in 1968 it had the exclusive honor of occupying the tables of the athletes, almost as if it were to bless the continuity of the value of Olympic ideal from then to now.

Two lands which today are wine producers par excellence seem to have disappeared in this review of the parallelism of civil, social, artistic, and oenological growth of our forerunners: Tuscany and Piedmont.

It is true that Caesar, returning from Gaul, praised the excellent wines of La Morra, today the Barolo capital, but to find firmer traces we have to leap ahead almost a thousand years. A nice legend seeks to assign to the Second Century B.C. the first traces of Barbaresco, the Barbaritium which served Caio Arrunte, a rich merchant of Chiusi, to convince the Gauls to join an alliance which allowed him to take revenge on the entire city for his grief as betrayed husband.

It is easier, though, to believe in the affair of a handful of Saracens (also called Barbareschi) who, around 900 A.D., invaded Alba but, betrayed by the abundance of good wine, all fell prisoner.

Those are years, around 1000 A.D., in which the Piedmontese wine production, well developed and appreciated for centuries, begins to acquire a precise identity, worthy of definitions fuller than the usual sequence of laudatory adjectives used by chroniclers and historians.

Edicts, bulls, and law texts begin to deal with wine production, they put into a normative context, they protect producers and consumers. But we must reach 1537 to see Barolo named officially in a banquet held in Alba in honor of Charles V.

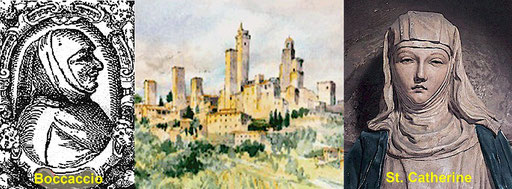

Regarding Tuscany, the honor of the first official recognition belongs to Vernaccia of San Gimignano, which by the end of Thirteenth Century was already object of a flourishing trade, and its export was controlled by city officials hired just for this purpose.

Dante Alighieri names it in the Divine Comedy; Giovanni Boccaccio invents a "rivulet of Vernaccia" in the fantastic panorama of the Paese di Bengodi; and St. Catherine of Siena finds a way of describing its miraculous action for the health of the infirm and weak.

Then, from century to century, it appears regularly in the chronicles, frm the mention of Sante Lancerio, bottler to Pope Paul II, up to the tables of Lorenzo the Magnificent, of pope Leo X, and of Ludovio il Moro, who wanted 200 flasks to enliven the nuptials of his nephew Gian Galeazzo with the daughter of Alfonso II, King of Naples.

It had the honor of being the first wine in Itlay recognized of “Denominazione di Origine Controllata,” on May 6, 1966.

We find traces of Chianti with a century's delay with respect to Vernaccia, in documents in which for the first time the word refers to the wine we all know rather than to the area from which it comes: it is clear it was harboring its splendor for some centuries, but only then did its undisputed supremacy emerge, object of strict regulations, intended to protect the quality, the price, the origin in townships and vineyards minutely detailed and catalogued.

From then on it had enormous success, the penetration of all the European markets, the enthusiasm of the reigning courts of Paris and London, the enrichment of the merchants of the straw flasks, seductive to the glance even before tasting the content.

If Vernaccia of San Gimignano holds the honor of being the first Italian D.O.C. wine, Est! Est!! Est!!! of Montefiascone, recognized only a day later (May 7, 1966), makes up for the delay thanks to the fascination of its illustrious and certain date of birth: the year 1110.

Until then, the wine produced on the slopes above the Lake of Bolsena up the habitations of Montefiascone were appreciated locally, praised by wayfarers, but present in the larger cities more in memories and tales than in effective trade.

THE WARRIORS

But that year the Emperor Henry V moved toward Rome at the head of a powerful army, to settle some questions with Pope Pasquale II.

Accompanying this expedition there was a bishop, Mons. Giovanni Defuk, who, having decided to take advantage of the touristic and dionysiac rather than the political aspects of the expedition, arranged to be preceded in every town by his cup-bearer Martino, whose duty it was to select the wine from the best cellars.

Reaching Montefiascone, Martino found it was not enough to write "Est!" near the door of the hosterly to indicate the presence of good wine. The agreed signal did not do justice to the quality of what he had tested, and, not having agreed on other signals, he decided to repeat that "Est!" three times, reinforcing its importance and authority.

The fame and glory of Est! Est!! Est!!! were born that day, from the moment in which Defuk tasted the wine and, won over by its softness, prolonged his stay by three days, returning at the end of the imperial mission, and staying there until his death.

He was buried in the local temple of San Flaviano, and for several centuries there was the custom of spilling a barrel of wine each year over his tomb stone.

The wines of this land must certainly have been capable of arousing great enthusiasm, to such an extent. It is sufficient to go just a few miles from Montefiascone to Orvieto, to find other evidence of wild passions.

Pinturicchio, called in 1492 to decorate the cathedral with frescoes, once he has tasted the wine in the local hostelries, required a clause in his contract "that he be given as much of that Orvieto wine as he might want".

But if it was all right for a painter to be a daredevil, what can we say of Pope Gregory XVI, who provided in his testament that his body was to be washed in Orvieto wine prior to burial?

Good wine, however, has always led the liveliest intellects at least to small transgressions, if we are to judge situations, pacts, and contracts by a yardstick other than that of hard cash.

It is the case of the Marchesi di Saluzzo, who in 1369 relieved of taxes and military obligations the inhabitants of Dogliani, as long as they paid an annual levy in kind, measured, obviously, in barrels of good Dolcetto. Or thirty years later, of the Bishop of Turin, Aimone di Romagnano, who, instead of money, required casks of Nebbiolo in payment of rent for the lands belonging to the diocese.

Each time we meet such episodes, we can be certain of one thing: that the wine that took the place of money was of a vastly higher quality than that produced nearby. Only because of this difference in quality could it enter into the heart and the expectations of the powerful man and induce him to give it a grater value than any sum of money.

The history of the Italian wines is a continual succession of fruitful crosses between peasant skill, literary exaltation and legislative protection. The wines mentioned so far have benefited from a vital gleam which made them emerge from the mass and presented them in a new light to the eyes of all.

But there is not a single wine of quality which has not, at least one in the past, been mentioned, even by a modest writer, as worthy of the table of the “lords,” of the “nobles,” of the “powerful.”

In more recent centuries, the glory of a wine is tied more to the response of the market, and the poet’s verse takes on the role of an authoritative support for a quality already accredited in mercantile circles.

This is the case with Marsala which was little aided by the passion of Rubens, who came to Italy to study the art of Titian and Caravaggio and returned to his country with his eyes full of our art and his baggage weighted down by an abundant supply of Sicilian wine.

More than a century must go by, and two English businessmen, John and William Woodhouse, must go to Sicily, before Marsala’s fame explodes throughout Europe.

STILL POETS

Then, with that wine, Giuseppe Garibaldi will toast to the success of expedition of the Mille, raising his glass with Alexandre Dumas, who is won over, but its irreversible success is already confirmed by the indisputable quality of the wine and by the way laid out by the English merchants.

In the same way, in Cinqueterre, there is neither verse nor literary quotation which can express the profound emotion on seeing those vines clinging to the limits of what is possible, to the rugged coasts which change from rocks to mountains in just a few yards, suggesting by its total absence the concept of hill.

Boccaccio and Petrarch dedicated verses and quotations to it, Pliny defined it "lunar wine".

Giosuè Carducci described it as the essence of "all dionysiac intoxication".

Giovanni Pascoli invoked the sending of a

few bottles "in the name of Italian literature".

And Gabriele D'Annunzio, the consummate master of terrestrial pleasures, declaimed its profound sensuality.

And yet, the ways of the world are not for this wine, no word is sufficient to impose it on foreign markets: one has to climb the harsh coasts of the vineyards, sweat under the rays of the sun magnified by the reflection of the sea, study one by one the wrinkles of the winemakers perennially suspended between sky and sea. Only thus is one overtaken by an insuperable desire to drink it, today as an hundred or a thousand years ago.

A MITH HUNDRED YEARS YOUNG

In a country so rich in history, and in oenological history, it can happen that the star of the moment can spread its roots everywhere, except in that lovely garden of tradition, of the past, of millennial tradition.

Francesco Redi, in his "Bacco in Toscana", sang the glories of many illustrious wines, including the fascinating Moscadelletto di Montalcino, sweet, blond, and sparkling.

And here it is that, at the threshold of the 20th century, a red wine is born in retaliation, full-bodied, of extraordinary energy, capable of improving beyond the temporal limits that in others mark the conditions of age and inevitable decadence: fruit of the extraordinary combination of mental "meanderings" and capacity of getting things done in a single man, Ferruccio Biondi Santi.

Brunello di Montalcino grows from the earth which seems to owe everything to nature, to spontaneity, to the benevolence of the climate, to the consummate traditions of the winemakers

It is born as a transgression, as a paradox, as a "spite" to the rhetoric of the earth that "knows", for the last three thousand years, how wine is made and must be made. It is the challenge of the future in a land built on the past.

It is a challenge won in a flash of time: less than a century was necessary to create the myth of Brunello in the whole world, without the witness of the historians, the verses of the immortals, the excesses of the powerful.

This alone is sufficient to give a great sense of security to Italian vintners today: the strength of an inimitable past behind us, and the knowledge that we can go toward the future without feeling that this treasure chest of experience will be transformed into a heavy burden.

RuvidaMente

RuvidaMente