Italy's glowing reputation with wine is due not only to the fact that it produces and exports more than any other country but that it offers the greatest variety of types, ranging through nearly every color, flavor and style imaginable.

Italian producers have moved rapidly

to the forefront of world enology, improving techniques to create wines of undeniable class in every region, north and south.

Their wines derive not only from native vines, which represent an enormous array, but also from a complete range of international varieties.

In the past it was sometimes said that Italians kept their best wines to themselves while supplying foreign markets with tasty but anonymous vino in economy sized bottles.

But markets have changed

radically in recent times as consumers in many lands have insisted on better quality.

For a while it may have seemed that the worldwide trend to standardize vines and wines was bound to compromise Italy's role as the champion of diversity.

But, instead, leading producers in many parts of the country have kept the emphasis firmly on traditional vines.

They have taken the authentic treasures of their ancient land and enhanced them in modern wines whose aromas and flavors are not to be experienced anywhere else.

Getting to know the unique wines of Italy is an endless adventure in taste.

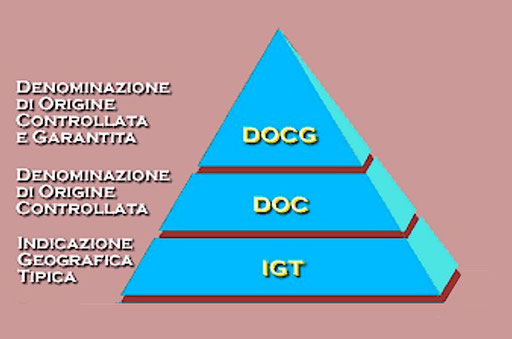

Experts increasingly rate Italy's premier wines among the world's finest. Many of the noblest originate in the more than 300 zones officially classified as DOC or DOCG -or, more recently, in areas recognized for typical wines under IGT. But a number of special wines carry their own proudly individualistic identities. Wine drinkers abroad, not always aware of the wealth of types (or perhaps overwhelmed by the numbers), have not always taken advantage of this unmatchable variety.

Quality Laws & Labels

Inhabitants of the Italian peninsula and islands have been making wine for thousands of years but it was only in the sixties that a comprehensive, nation-wide program regulating the entire sector was adopted. Although techniques of cultivation and winemaking reached a relatively high level under the Roman Empire, the entire enterprise rested on shaky foundations.

Science was in its infancy and most inquiries into natural phenomena were primarily speculative in nature so that theory was virtually everything, while technique was based essentially on empiricism. Observation and experience determined how certain processes might be conducted with reasonable expectation of successful outcomes.

For example, some ancient writers on agricultural themes suspected that "creatures" or "things" that could not be seen by the human eye caused the fermentation as well as the spoilage of wines.

But they could go no further because they lacked microscopes, which would have permitted them to see those things and gain some understanding of how they functioned.

Yet their empirical approach did permit some ancient winemakers to produce relatively good results. And some of the ancient techniques have been retained or revived. For example, raisin or passito wines like Amarone, which are obtained from partly dried grapes, are increasingly attracting attention and fans, although only a few decades ago most producers and critics regarded them as archaic survivals of outmoded and defective winemaking techniques.

Survivals they certainly were, for the Greeks and Romans were making them more than 2,000 years ago. And the technique solved, at least in part, an extremely ancient problem, how to preserve wines, which tended to go bad soon after the harvest.

Drying boosted the grapes' sugar content so that, when the fruit was pressed and the must was added to the wine already made, a second fermentation occurred.

That increased the level of alcohol, a preservative, and extended the life of the wine as well as altering for better or worse its sensory characteristics.

Practices familiar to wine consumers today were already common in Classical times.

Ancient sources report that identifying labels were often engraved in Roman wine containers. Consumers were able, theoretically at least, to identify the producer, source and type of a particular wine. But there have always been some unscrupulous dealers who would alter the information on the labels or dilute the wines.

In nearly all countries, misrepresentation was not unusual many decades ago but in Italy the impact was limited since most wine was consumed in the same area where it was made. The consumer, therefore, often knew the producer and that familiarity provided a substantial degree of assurance.

With the rise of a global wine market, the need for a more formal type of guarantee led to the creation of the modern wine appellation or denomination system.

In the 19th century wine became a commodity, widely available on markets throughout the world, only with the development of steam-powered transportation by land and sea. It was then that many Italian wines began to travel outside of their production zones.

It was also in the 19th century that scientists began to lay the theoretical and practical foundations of modern winemaking.

Eventually, new modes of transportation and technology were to sweep away many ancient winemaking practices, in the process creating pressures for sweeping change in many sectors. As market demands increased, so did the need to guarantee and protect the origin of Italian wines.

Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita

In 1980, Italian authorities established a superior classification of DOC wines.

The roll call of Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita (DOCG) products began with five wines, Brunello di Montalcino, Vino Nobile di Montepulciano and Chianti, all Tuscan, and Barolo and Barbaresco, both produced in Piedmont.

All five had solidly established international reputations and all but one, Brunello (developed since the middle of the 19th century), had been produced for centuries in one form or another (for example, Barolo seems at one point to have been vinified as a sweetish wine and Chianti as a white).

The selection of the five for elevation to the peak of the Italian wine pyramid was, therefore, a foregone conclusion: today, a total of 78 wines have been awarded the prestigious DOCG status.

The five wines are derived primarily from only two varieties, Nebbiolo for Barolo and Barbaresco and Sangiovese for the three others.

The two grapes are native to Italy as are the varieties used in the production of most of the 78 other wines added to the superior category during the last 40 years.

While, the "international" grapes employed in the making of some of the other DOCG wines have been cultivated in their production zones for a century or more and are completely acclimatized.

A DOCG wine must meet standards that are stricter than those stipulated in DOC regulations. One of the principal differences is the lower yields imposed by the DOCG rules.

The reductions in output have probably done more to boost the quality of the wines than any other provision in the production codes.

The rules also require in-depth chemical analyses for all DOCG wines. Laboratories recognized by the government must carry out the examinations of the wines' physical composition.

Once the analyses have demonstrated that the chemical properties are in accordance with the standards specified in the DOCG regulations, committees consisting of expert tasters sample each producer's wines.

The committees can reject wines that fail to meet the specified sensory standards or instruct the producers to take steps to remedy deficiencies before approving or discarding the product.

Upon receipt of a favorable report on the outcome of the chemical and sensory analyses, the producers' consortia or, less often, some other official body issues small numbered seals that fit over the corks in the bottles of DOCG wines.

Strict controls are applied to ensure that the number of seals issued corresponds to the amount of wine that can be produced in accordance with the limitations of the regulations.

Among Italy's 20 regions, Piedmont currently leads the way with 19 DOCG wines. In addition to Barolo and Barbaresco, the most important are Gattinara and Ghemme, both dry reds made from Nebbiolo, also known in northeastern Piedmont as Spanna. There are also two white DOCGs, the sweetish Asti, including Asti Spumante and Moscato d'Asti, and the dry Gavi or Cortese di Gavi. Not to be forgotten an unusual, a bubbly red dessert beverage, Brachetto d'Acqui.

The Veneto is in second place with 14 DOCG appellations led by the red full bodied Amarone della Valpolicella, the dry red Bardolino Superiore and two whites outstanding whites: the dry Soave Superiore and the sweet Recioto di Soave.

Tuscany, Piedmont's perennial rival in the enological sector, ranks in third place with 11 DOCG wines led by Chianti (it has been divided into two appellations: Chianti Classico, the oldest production zone located in the center of Tuscany, and Chianti, which consists of seven subzones. The subzones, clustered around the Classico zone, are: Colli Aretini, Colli Fiorentini, Colli Senesi, Colline Pisane, Montalbano, Rùfina and Montespertoli.)

Not to be missed, the classic Tuscan DOCG reds: Brunello di Montalcino, Vino Nobile di Montepulciano, Morellino di Scansano. And the historic dry white Vernaccia di San Gimignano.

Today, within the DOC and DOCG zones well over 2,000 types of wine are produced. They may be defined by color or type (still, bubbly or sparkling; dry, semisweet or sweet; natural or fortified). Or they may be referred to by grape variety (e.g. Trentino has 26 types of wine including 20 varietals).

Wines may also be categorized by age (young wine to be sold in the year of harvest as novello or aged as vecchio, stravecchio or riserva) or by a special subzone as classico or superiore.

The term superiore or scelto may also apply to a higher degree of alcohol, a longer required period of aging or lower vine yields.

DOC: Denominazione di Origine Controllata

Throughout history, the inhabitants of the Italian peninsula have seldom known a period of tranquility that has endured for any length of time.

The 19th century and first half of the 20th were exceptionally tormented eras. In such conditions, it is understandable that the country's agriculture lagged behind in the effort to adopt more scientific and modern methods of cultivation and production.

There were enterprising producers, many of whom shipped their wines to foreign markets and received awards for the quality of their products.

There were enterprising producers, many of whom shipped their wines to foreign markets and received awards for the quality of their products. And some regions showed commendable initiative in adopting regulatory measures that, while they were far from sweeping, laid the groundwork for progress. For example, the Grand Duke of Tuscany drew the boundaries for the production zones of important regional wines in 1716, creating the first official appellation in the history of winemaking.

The real revolution in the Italian wine sector began in the 1960's. When the European Common Market coalesced in the decade and a half following the end of World War II, Italy was assigned as its principal task the provision of darkly colored bulk wines with high alcohol levels for blending with the weaker wines of the north-in the country itself and in Europe beyond the Alps.

At that time the European Economic Community assumed that consumption of wine throughout the continent would remain the same or even increase.

However, lifestyles changed rapidly and, as a result, consumption declined abruptly, dropping to less than

half of postwar levels, while the market for bulk wine shrank accordingly.

In addition, many Italian producers rejected the idea of turning out second-class wines regarded as suitable only for blending with other beverages.

In the early 1960's, Italy abandoned the sharecropper system, which had been the organizational model in the agricultural sector since the Middle Ages.

The action set off a massive exodus from the countryside with many thousands of farmers and farm workers streaming into the cities where, with the "Italian economic miracle" booming along, they could find work in factories that was more secure and less onerous than farming.

More ambitious grape growers compensated for the loss of laborers by mechanizing operations, introducing tracked tractors, for example, which could function on the slopes of hills. Changes in the layout of vineyards to accommodate the new equipment radically altered the appearance of the countryside in many parts of Italy.

The abolition of sharecropping was accompanied by the creation in 1963 of the controlled wine appellation system, known in Italian as Denominazione di Origine Controllata (DOC).

Experts quickly set to work implementing the DOC law by surveying the wines made throughout the country and writing production codes for each of those whose producers requested certification.

It was a Herculean task because Italy cultivates more varieties of grapes than any other country and produces a bewildering array of wines. Demand for certification was brisk and the authors of the production codes worked at high speed.

The production codes delimit the zones in which the wines originate and specify type (or types, since a denomination may include a range of versions), color, grape varieties, minimum alcohol levels, maximum yields in grapes per vine per hectare and wine from grapes, basic sensory characteristics, maturation (in wood or otherwise and possibly in sealed tanks), required minimum periods of aging and special designations identifying particular sub-zones, such as classico or superiore.

Producers' consortia, already existing or formed as a consequence of the adoption of the DOC system, are generally charged with overseeing production in each zone to ensure compliance with the regulations.

A National DOC Wine Committee, established by the Italian Ministry of Agriculture, must approve all new production codes or any changes to the existing regulations.

The DOC law also established registers, usually maintained by the local Chamber of Commerce, in which all growers and winemakers must enter their vineyards and report their production of grapes and wines.

The national (carabinieri) and local police forces and anti-fraud units inspect and regulate wineries and wine shipments.

Because of the haste with which the production codes were drawn up, especially in the early days of the DOC system, the compilers tended to base the rules on traditional practices, which in many cases were outmoded.

Many producers chafed at what they regarded as the narrowness of the production codes, which they argued prevented them from adopting modern methods and satisfying current market requirements.

In response, the National DOC Committee began to approve revisions of numerous production codes, while the law governing the entire system was amended several times and entirely updated in 1992 with passage of Law No. 164.

Today (2024), 341 wines have qualified for DOC status since the system was introduced in Italy.

And the authorities in the sector continue to approve new production codes, although not at the pace of earlier years.

Despite the proliferation of appellations and 40 years of increasing familiarity with the system among wine consumers worldwide, however, there is still much confusion about the real meaning of the term Denominazione di Origine Controllata.

Many consumers assume that it refers to quality and in a sense it does, however only more knowledgeable consumers know that it refers to the guarantee of origin of the grapes and adherence to the methods specified in the regulations governing the production of the wine.

The DOC law has resulted in a substantial improvement in the quality of Italian wines. It has encouraged producers to invest in land and equipment, to conduct or sponsor research and to compete with the finest wines of other producing countries. Many of the 2,000 types of wine currently covered by the DOC regulations are still largely unknown outside of Italy or, in some cases, their production zones.

The DOC has encouraged producers to look beyond the local market and the steady improvement in their wines' quality has enabled them to meet world competition.

IGT: Indicazione Geografica Tipica

In 1992, the Italian government adopted Law No. 164, which modified and expanded the DOC system.

Among the law's most sweeping innovations was the introduction of the

Indicazione Geografica Tipica (IGT) category. By the end of 2002, the National DOC Wine Committee had recognized about 200 IGT classifications.

The IGT opened up new paths for winemakers who wanted to venture outside the relatively strict confines of the DOC and DOCG categories without, however, making concessions on the level of quality.

The IGT regulations require use of authorized varieties and most of the production codes adopted to date provide for the use of one type alone or in a ratio of at least 85% to other approved grapes. Some regions of Italy have long produced such varietal wines, especially Friuli-Venezia Giulia and Trentino-Alto Adige in the northeast.

Others have focused their production primarily on blends of different varieties. Producers of Chianti Classico, for example, can make their wine from Sangiovese alone or with a blend of Sangiovese (at least 80%) and native varieties like Canaiolo and Colorino or international grapes like Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon (a maximum of 20%).

If producers make a wine from Merlot alone, they cannot use the Chianti Classico DOCG appellation. In the past, that Merlot, no matter how fine it might be, could not receive any denomination. It had to go to the market as a vino da tavola.

The IGT regulations have substantially altered that situation.

The IGT wines are identified with specific territories, most of which are larger than the zones specified in the regulations for DOCGs and DOCs. Some are region-wide, as in the case of Toscano in Tuscany and Sicilia on Sicily, while others are limited to a valley or a range of hills.

For consumers, the IGT primarily means a wide range of wines of good quality available at highly competitive prices. In recent years, DOC and DOCG wines have accounted for about 20% of Italy's total production.

With their establishment of the IGT category, Italian authorities have set their sights on achieving a ratio of appellation wines to total domestic output of 50% and more.

BACK TO

RuvidaMente

RuvidaMente