The tomato is perhaps the most emblematic of the foods characteristically associated with Italian cuisine. Anyone in any part of the world who has come into contact with Italy’s gastronomy, whether occasionally or on a daily basis, is convinced that the tomato is a fundamental and inalienable element of it. In reality, the tomato’s entry into the Italian pantry occurred relatively recently, as did its “matrimony” with another cornerstone of Italian cuisine, pasta. The 150th anniversary of that union was celebrated only in the last few years.

The path along which the tomato made its way to the kitchens and tables of Italy was a long one that began in a vast area in South America, in what are now the countries of the Peru, Ecuador and Bolivia, where the original species grows wild.

After its domestication, the tomato was cultivated in pre-Columbian times in an extensive area that included Mexico and the rest of Central America.

The first written notice of the plant’s existence was provided by Bernardino de Sahagún, who mentioned it as an ingredient of a sauce that was sold in the huge market at Tenochtitlán (Mexico City) by women venders who “usually blended it in the following manner: aji [hot red pepper], pepitas [pumpkin seeds], tomatl [tomato] and chiles verdes [hot green peppers] and other things that make the juice highly savory.”

Other than as a sauce, ready for use, that was sold in the market square, tomatoes were served at important meals in Mexico along with the meat of turkeys alternating with layers of the flesh of dogs.

However, the tomato also often appeared in daily cooking, stewed in the pot along with turkey or fish “in addition to red pepper and pounded pumpkin seeds.”

While Christopher Columbus did not take the tomato back to Spain from his four voyages to the New World, the Conquistadores who followed in his footsteps certainly did, as a curiosity they had encountered in Mexico.

THE FIRST LANDING WAS IN SPAIN

The tomato appeared in Spain in the early years of the 16th century, where it was described as a magical and medicinal plant. According to the explorers, who took back the plant’s seeds, the tomato was regarded in its land of origin as a cure for various ailments but was also used in the preparation of magical potions and aphrodisiacs. Its roots were soon being sold as a magical touchstone.

Other often picturesque descriptions were soon provided by adventurous pioneers who began to cultivate the plant in order to learn more about it and who, prompted by natural curiosity, tried eating it. They described it as being similar to eggplant but rather unappetizing and not at all nutritious.

The author of a 16th-century list of herbs observed that “these fruits [tomatoes] are eaten after being cooked in the paëlla (pot) in oil or with garlic but they are noxious and harmful.” In another text published a century later, tomatoes were still being described as “a poor and defective food.”

The tomato reached Paris on the eve of the French Revolution from the south of France, where the plant grew vigorously because of the favorable climate and was much appreciated.

In the north, the cold seared the fruits, which as a result had little flavor. The tomato, like the “Marseillaise,” was immediately accepted in the capital.

With an eye to the political situation and a keen sense of business, innkeepers seized on this novel food and were soon serving it in a thousand ways.

That newfound popularity was due in great part to the tomato’s brilliant color, which matched the mood of the times.

The tomato reached Italy, officially at least, in the 17th century.

It was brought into the country by the Spanish but they did not at the same time introduce any culinary preparations in which the fruit was employed.

SLOWLY, FROM SPAIN TO SOUTHERN ITALY

It apparently required more than a century and the ingenuity of the southerners, stimulated by chronic famine, to bring the tomato and pasta together. Who took that fateful step, it is impossible to say but it appears that some teamsters in the Trapani area, who were soon emulated by the rural inhabitants of western Sicily, started the practice of adding a substantial amount of tomato cut into slices to the water in which macaroni or vermicelli was boiled.

In Campania, the adopted homeland of pummarola or tomato sauce, cultivation of tomatoes on a large scale was late in getting under way, despite the fact that the plant was first grown in the region as early as 1596.

What is certain is that a dish of macaroni flavored with a bit of cheese was selling at the end of the 18th century for two centesimi (cents) in the inns of Naples. In the north, meanwhile, tomatoes were cultivated as ornamental plants.

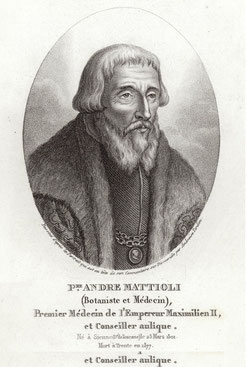

The Sienese botanist Pietro Andrea Mattioli (1500-1570) was the first in Italy to call the tomato by the name it has since retained in Italian, pomo d’oro or golden apple.

Mattioli was referring to one of the colors the tomato assumes during its ripening.

While Italians refer to the fruit as a pomodoro (the plural is pomodori), the French, English,

Spanish and Germans continue to use terms directly derived from the name the Nahuatl Indians of Mexico gave it, tomatl. In discussing the eggplant, Mattioli reported in 1544 that “another species, known as Pomi d’Oro, has been

brought into Italy in our day.

The fruits are compressed in shape, like rose apples, and grow in clusters.

At first they are green in color and from some plants are as red as blood when they ripen, while others are the color of gold. Both are eaten in the same way.” That “way” was boiled, cut in slices, dredged in flour and fried.

THREE CENTURIES, BUT IT WAS WORTH IT

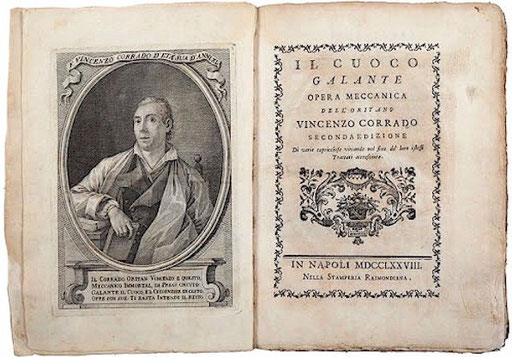

Within three centuries, the tomato had been accepted everywhere in Italy. In Il Cuoco Galante (“The Gallant Cook”), one of the first complete Italian cookbooks, Neapolitan Vincenzo Corrado (1734-1836) wrote that

“various tasty dishes can be made from the tomato. Sauce prepared from them can be used to flavor meats, fish, eggs, pastas and vegetables. A good cook can easily create delicious tidbits from them and a universal sauce [since it can be used in numerous ways]. The tomato not only pleases the palate with its flavor but also benefits the body, since its acidic juice aids digestion, particularly during the summer season when people’s stomachs are flaccid and prey to nausea because of the overpowering heat. These summer tomatoes are round and of a saffron color. They have a skin that must be removed by rotating them over the coals and plunging them afterward in boiling water. It is possible to remove the seeds, to assure more delicate and satisfying preparations, by opening a hole at the point where the stem joins the tomato or cutting the tomatoes in half.”

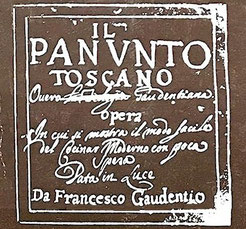

Earlier, however, the literature of the tomato was rather scanty, which is the most convincing evidence that the plant was not widely diffused. One of the first publications dedicated to the cultivation of tomatoes was Giovanni Francesco Angelita Roco’s I Pomi d’Oro, issued at Recanati in the Marches in 1607. However, it was not widely circulated. A century later, in 1705, Francesco Gaudentio, lay coadjutor for provisions of a community of Jesuits in Rome, provided the first Italian recipe for cooked tomatoes in his Panunto Toscano, the manuscript of which is preserved in the Communal Library of Arezzo.

The recipe:

“These fruits are very similar to apples. They are cultivated in gardens and are cooked in the following way: pick the tomatoes, cut them in pieces and put the pieces in a pan with oil, salt, chopped garlic and wild mint.

Stew them, frequently stirring the mixture. The dish will be even better if you add a bit of tender molignane [eggplant] or white cucuzze [squash].”

Only in the late 18th and early 19th centuries was the tomato “officially” endorsed by gourmets and leading chefs, beginning precisely with Corrado, a Celestinian monk who, from his privileged observation post in Naples, reported that he had tasted his first “leg of kid coated with tomato paste and larded with lardoons and spikes of rosemary and roasted in the oven with butter and herbs.”

In the third edition of Il Cuoco Galante, published in 1773, the attentive gourmet listed the following recipes involving tomatoes: (from Treatise One - Pythagorean Fare)—stuffed with veal, dressed with salpicanti (saupiquet, a pungent sauce), stuffed and cooked in butter, filled with greens, stuffed with rice, alla Corradina, stuffed with fish, cooked in truffle sauce, alla napolitana, in croquettes, in fritters and in a pudding.

Two years later, Francesco Leonardi, former cook to Catherine II the Great, Empress of all the Russias, published his Apicio Moderno. In the 2nd

edition of that work, which appeared in 1797, there is the first recipe for culì (or coulis), a tomato sauce in the French style that was then highly fashionable. However, there is no

mention of its possible use with pasta. A further 40 years were to pass before the first recipe

for vermicelli col pomodoro (fine spaghetti with tomato) appeared. However, it is always possible that many housewives had already been combining tomato and pasta for some time, although such

a practice was not widely diffused at the time.

The fascinating Neapolitan watercolors of the early 19th century always depict maccaronari or macaroni eaters stuffing themselves, using their hands in the process, with pasta in bianco

1839: "SPAGHETTI WITH TOMATO SAUCE"

IS OFFICIALLY BORN

The first historical vermicelli co le pommodoro was described in 1839 by Ippolito Cavalcanti, Duke of Buonvicino (1787-1860), in “Cucina Casareccia in Dialetto Napoletano” (“Home Cooking in Neapolitan Dialect”), an appendix of La Cucina Teorico-Pratica (Theoretical and Practical Cooking).

In Rule 10 of the chapter devoted to sauces, Cavalcanti adds:

“It [tomato] is good if you want to prepare macaroni or any other type of small pasta. You should not put the sauce on top of boiled meat, eggs, chicken and fish, which are good with a bit of butter. Make this excellent sauce so that you can flavor vermicelli but, if you baste it with oil, it will be even better and more savory.”

Thirty years later, numerous preparations based on tomatoes were described in La Cuciniera Genovese (The Genoese Cook), published in 1864-65 in Genoa by G.B. Ratto, and La Vera Cuciniera Genovese (The Real Genoese Cook), “compiled” by Emanuele Rossi and published in 1867 in Livorno. The recipes ranged from simple to concentrated purées, reductions “suited to flavoring soups and other dishes” and sauces that are used in basting “meats and boiled chickens and veal cutlets in the Milanese style,” and in thickening soups served with bread cut in slices and toasted.

Afterward, every Italian region developed its own characteristic dishes, although the popularity of some preparations, with numerous variations, extended beyond regional boundaries. Piedmont, Umbria, Latium and Sardinia came up with recipes for stuffed tomatoes, while Tuscany invented pappa col pomodoro (tomatoes cooked with oil, garlic and basil). The Neapolitans gratinéed tomatoes, while the Calabrians roasted them, in addition to stuffing them with cannolicchi (small pasta). The Sicilians like them gratinéed as well.

That brief survey of the history of the tomato in Italy shows how slowly and with what difficulty the fruit was introduced into everyday Italian cooking.

AND THANKS ALSO TO THE "AMERICAN TOUCH"

It really became a common food only in the 19th century, during which the industrial canning of tomatoes began to develop in parallel with consumption of the fresh product.

However, it should be noted that the first bottled tomato sauce to be produced on an industrial scale was American, the creation of William Underwood of Boston, who in 1835 opened the first factory for the canning of tomatoes.

Meanwhile, the ancestor of tomato concentrate can be traced to Parma.

It was the famous conserva nera (black preserve) that was described in 1811 by the agronomist of Count Filippo Re as follows: “The tomato is used when it is fresh but in addition the juice is pressed from it and it is reduced to a solid consistency, so that it can be used…throughout the course of the year.”

Credit for having been the first in Italy to publish a recipe for the tomato goes to Vincenzo Corrado in the 18th century or nearly three centuries after the first voyage to the New World of Christopher Columbus. The tomato’s official debut in Italian cuisine was a rather timid entry, a simple but tasty preparation that at least provided a hint of the future that lay ahead of the fruit on Italian tables.

Pomodori alla Certosina, Vincenzo Corrado, 1781:

Fill the tomatoes with anchovy sauce, truffles and the flesh of fish cooked in oil and pounded altogether and

flavored with chopped greens. Fry the stuffed tomatoes in oil and serve them with puréed tomatoes.

Fifty years later, or 350 after the fateful events of 1492, another writer, Ippolito Cavalcanti, assisted at the birth of what has been considered ever since as Italy’s national dish, spaghetti with tomato.

Viermicelli co le Pommodoro, Ippolito Cavalcanti, 1839:

Pick four rotola [a Neapolitan measure of weight, equaling about 33 ounces, therefore 8 1/4 pounds] of tomatoes. Cut out any blemishes, remove the seeds and water and boil the fruit. When the tomatoes are soft, pass the pulp through a sieve and cook down by a third. When the sauce is sufficiently dense, boil two rotola [four pounds] of vermicelli. Drain the pasta and add it to the sauce along with salt and pepper. Stir and cook the mixture until the sauce has dried and serve.

Tomato sauce, now a standard addition to innumerable culinary preparations, which it flavors, improves, transforms and enriches, was also codified at that time. The sauce is a fundamental element of Italian cuisine, since it can be combined with almost any other food, including vegetables, fish, eggs and meat. Unfortunately, it has also often served as a means of “Italianizing” any sort of raw material or recipe borrowed from some other gastronomic tradition.

Salsa di Pomodoro, Ippolito Cavalcanti, 1839:

Remove all of the seeds and liquid from two rotoli [four pounds] of tomatoes and boil them. Pass the tomatoes through a sieve and boil the pulp with a handful of parsley and basil, which should be removed before the sauce. is strained. Put the extract in a pot, melt four ounces of butter and blend it into the sauce. Add salt and pepper and serve.

The same approach to making tomato sauce was followed by Pellegrino Artusi in his La Scienza in Cucina e l’Arte di Mangiar Bene (Science in Cooking and the Arft of Eating Well), the first truly organic treatment of the Italian cuisine that everyone knows and appreciates today. The publication of that recipebook in 1891, in fact, be regarded as the official birth of modern Italian gastronomy.

Salsa di Pomodoro, Pellegrino Artusi, 1891:

Finely chop 1/4 of an onion, a clove of garlic, a piece of celery as long as a finger, some basil leaves and as much parsley as you wish. Flavor with a bit of oil, salt and pepper. Chop up seven or eight tomatoes and put everything in a pot. Cook, stirring from time to time, and when you see that the sauce has condensed into a thick cream, pass the purée through a sieve and serve. This sauce has many uses, as indicated in the various entries. It is good with boiled meats and excellent for flavoring pastas along with cheese and butter. And it is also good in preparing risotti.

Following the appearance of Artusi’s book, the number of preparations in which the tomato played a leading or major supporting role grew rapidly. That was as true of the cuisine of the poor as of that of the courts or the grand hotels and of the recipes written by hand and passed down from mother to daughter or printed in books on culinary themes that increasingly received serious consideration from publishers.

BACK TO

RuvidaMente

RuvidaMente