All over the world and in Italy too, a lot of people are convinced that pasta was invented in

China and that Marco Polo brought it to Italy in the 13th century. However, is enough to read what is written in "Il Milione", the book in which Marco Polo relates about his voyage in Far East, to be convinced of the contrary: that at the time, in Italy, pasta was a very

common food.

Marco Polo, in fact, writes that in China he saw and tested "lasagne similar to those that we prepare with wheat flour".

So, who invented pasta? We have always the bad habit to go in search of who invented something, and where and when.

But in the case of food it is impossible to give a sure answer to these questions. Mainly when we refer to a food that today is the basic food of a nation, if there is an "inventor", it is always hunger, famine, desperation, fear of the future. And this is even more true in the case of pasta.

To give a synthetic answer we can say that pasta was invented - and could not be invented other than - by a population who lived in a big town, center of political and military power, in the heart of a geographical area where cereals were the basic ingredient of the diet.

Cereals, and particularly wheat, have been for millennia the basic nourishment of peoples living in the Mediterranean area.

Their diffusion was due, in addition to the nutritional value, to the fact that, in comparison with other agricultural products, cereals had an extended-storage capacity.

To be eaten, cereals had to be milled and then the flour was cooked in two different ways: mixed into a boiling liquid, like water, broth or milk (like our polenta or semolino), or worked into dough and baked in the oven or over fiery stones to prepare bread or focacce.

These two different ways to prepare grain were common in all the countries of the Mediterranean area and for centuries the technique was always the same, with no changes.

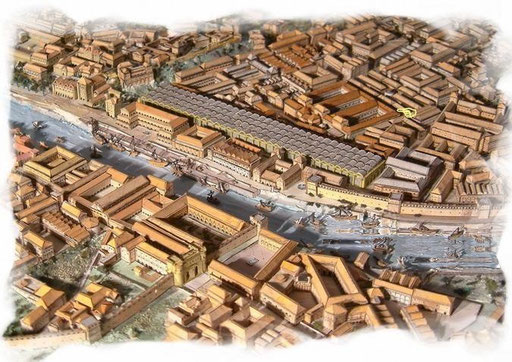

But, starting from the 3rd century B.C., thanks to its increasing power, the domination of Rome

spread from the geographical center of the Mediterranean sea as far as the borders of the world known in those times.

1.5 MILLION PEOPLE TO FEED

In the meantime, the city of Rome increased its population from 100,000 inhabitants in 264 B.C. to 313,000 in 130 B.C., to 1,000,000 in 55 B.C., to 1,500,000 one hundred years later, under the empire of Caesar Augustus. Try to imagine how difficult could be, 2,000 years ago, to manage a town of 1,500,000 people!

The main striking problem was to guarantee enough food to his inhabitants: in fact, the agricultural production from the country-side around Rome was not sufficient for such a huge population, and too expensive in comparison with the goods coming from the conquered countries.

To resolve this problem, the Roman government organized a supply system, first from Southern-Italian regions (in 70 B.C. Sicily produced over 500 millions lbs. of wheat), then, North-African and Middle-East countries.

During the empire of Caesar Augustus, each year, a fleet of 300 ships conveyed from Egypt to Rome 270,000,000 lbs. of cereals. And 350,000,000 lbs. from North-African countries, 80.000.000 from Sicily, and smaller quantities from Sardinia, Syria, Spain, for a total amount of 800,000,000 lbs.

In spite of this enormous availability and organizational efforts, due to frequent famines or shipwrecks, it could happen that in the Roman granaries there was not enough wheat to satisfy the entire population.

In addition, the storage of such huge quantities of grain created a further problem: is easy to suppose which could be the sanitary conditions of the granaries of that time, with no chemical products or modern techniques to protect goods from animals, insects and parasites.

Just to give you an idea of the problem we can remember that in 62 A.D. Nero was obliged to throw in the Tiber river all the grain stored in the granaries because it was so infested with parasites that it was no good for food.

The main part of this wheat was distributed monthly, free of charge or at special price, to lower-classes whose first problem was to stop the action of insects and parasites, using two different techniques, toasting or milling the grains.

The toasted grain could be stored for some time and were milled before cooking them in boiling water, to prepare a sort of polenta.

On the contrary, the transformation of wheat in grain flour was only a temporary solution. It could be infected not only by new parasites, but also by humidity and mould.

To avoid this risk, people used to bake bread and focacce twice over, transforming them into a sort of sea-biscuit, a product easy to store for some time. Or to work flour into dough, to roll out it in thin foils and let it dry in the sun.

THE FIRST DRIED PASTA IN THE HISTORY

The result was "dried pasta", the first dried pasta in the history, preservable for long time (at least one year and more) and usually cooked mixing it in vegetable soups, the famous Roman pultes.

Therefore, the origins of pasta are not so glamorous and noble as we would like: pasta is a humble product, invented in poor families to prevent a basic food from deterioration and to settle a provision in fear of failing the next public distribution of cereals, due to famine in the producing areas, storms over the ships that carried them to Rome, or a more dangerous infestation in the Roman granaries.

In fact, the production of pasta started in Rome during the imperial period, or alternatively in a place where, in the same moment, these three conditions took place:

1:

A town crowded by over one million of inhabitants, depending on external supplies of food, with no integration with the surrounding country-side.

2:

A population always in fear of hunger because of subsequent famines

3:

The risks connected with the storage of grain, subjected to easy deterioration, risks moreover serious inside single families, depending from the monthly assignments of the public granaries and unable to find or buy other kinds of food.

Thanks to its poor origin, pasta had no place in the pages of writers, historians and poets of the imperial age.

There is no mention of pasta because when food becomes the subject of history, it is the food displayed on the tables of the rich and the powerful who, in imperial Rome, undoubtedly did not eat pasta.

On the other hand, if a poet praised the dream of the country life, in which rustic and simple foods are protagonist of the daily table, also in this case pasta was neglected, because it had no relationship with the pleasures of country life: pasta is a product invented to survive in a huge town, and is not a good subject for a poet.

Unless the poet is a non conformist person like Horace, who liked to show off attitudes in contrast with those of the powerful people living around him. In the VI Satire of the 1st Book, as a proof of a quiet and healthy life he wrote "...then (in the evening) I come back home to have supper with a bowl of leeks, chick-peas and lagane".

FROM LAGANE TO LASAGNE

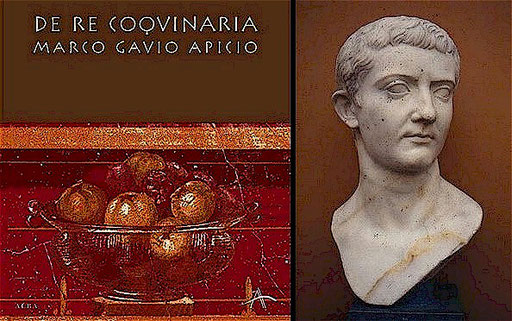

Well, those "lagane", a word still used in many Southern Italian regions, are nothing but our "lasagne". And Apicius, the author of De Re Coquinaria, the first cookbook ever written, makes use of them in many dishes, never minding to explain how to prepare them.

But Apicius always gives the reader careful directions about every step of the recipes, and this is a mark of how common was the preparation of lagane in that time in Rome.

However, if we compare the two texts, we discover that there is an essential difference between Horace's and Apicius lagane.

However, if we compare the two texts, we discover that there is an essential difference between Horace's and Apicius lagane.

The first are poor ingredients thrown in the pot to prepare a simple and frugal meal. In the recipes of Apicius they are elements of a refined and elaborated dish, that requires long cooking time and the ability of a chef. The first are lagane of dried pasta, the second are made with fresh pasta.

This is a very important distinction: in the following centuries, when writers and historians will mention "pasta", it will be always fresh pasta, prepared in the kitchens of the kings and the nobles, worked into dough with eggs, cut into strips or squares, rolled up, stuffed with a rich mixture of meat, fish and vegetables: agnolotti, tortellini, ravioli.

But fresh pasta was a food of the rich and the powerful long time before Rome reached the status to invent "dried pasta".

The oldest testimony of pasta in Italy is in Cerveteri, inside an Etruscan tomb of the 4th century B.C. (the tomb of a very rich man, with magnificent altorilievi): the two central columns are decorated with a stuccowork reproducing all the tools necessary (even today) to prepare pasta: the rolling-board, the rolling-pin, the ladle for the water, the knife to cut the dough and the roller-knife to give to lasagne the finishing touch of a waved edge.

On the other hand, we are lacking of testimony of dried pasta for about one millennium. Only after year 1000 A.D. we can find traces of pasta with a shape different from lasagne.

The first new shape is vermicelli, whose production, of certain Arab origin, started in Sicily and from there spread all over Italy.

And, then, maccheroni, a famous word to indicate different shapes, like gnocchi or pellets, all made squashing the dough with fingers or special tools.

THE PASTA TAKES SHAPE

It is only after the 14th century that we can notice a growth in the creation of new shapes of pasta, but is always a local occurrence and not a sign of an evolution toward industrial production: pasta remains an emergency food, a supply for the future whose consumption became usual only because obliged to renew the provisions year by year.

In the city of Naples, that we all identify as the world capital of pasta, until the 17th century lasagne or vermicelli were not a basic food.

On the contrary, up to that time, Neapolitans were called Mangiafoglie, leaf-eaters.

But under the Spanish domination, marked by a foolish management of the public administration, the problems connected with the supply of grain became even more serious and frequent, exactly as it happened during the Roman empire, and forced the population to make use of dried pasta as a provision.

A dried pasta that, thanks to the introduction of new machines, like the kneading-trough and the press, was far different from the original Roman lagane and very similar to the pasta that we all enjoy today.

The persistence of this state of emergency throughout the entire Spanish domination, over a period of two centuries, turned Neapolitans from Mangiafoglie into Mangiamaccheroni, maccheroni eaters, a new title that marked them all over the world since 17th century .

Once more pasta becomes the symbol of a nation not for its gastronomical merits, not because it was a fashionable food able to deal out pleasures, but only for its skill in fighting hunger and lack of resources.

As a matter of fact, in the same years and through the beginning of the 19th century, the most refined cuisine triumphed on the tables of the rich and the nobility, plentiful with fresh stuffed pasta that, little by little, became a gastronomical habit of the wealthy classes, who not always prepared it at home, but more and more bought it in the fresh pasta shops that, mainly in Northern Italian cities, were opened by specialized craftsmen.

After this quick stroll through the centuries, we can quietly state that dried pasta is a culinary invention uniquely and typically Italian and whose preparation and consumption spread throughout Italy because of a combination of numerous events and historical-social conditions.

At the same time, pasta appears to have been biding its time for centuries, awaiting a catalyst that would provide the necessary impetus toward achievement of its full potential-elevation to the status of a primary food capable not only of satisfying hunger but also of pleasing the palate. Until the 18th century, consumption of pasta was essentially confined to the poor, who adopted it principally because of its extended-storage capacity and its outstanding nutritional value, not because they found it particularly appetizing. It was customarily boiled and eaten alone or flavored, at most, with a bit of grated cheese.

As a dish, it had little or no subtlety and no fuss was made in presenting it. Vermicelli was clutched in the hand and lifted to the mouth without ceremony.

THE HAPPY MARRIAGE BETWEEN PASTA AND TOMATO

It was only when it was combined with tomato that pasta became a real "dish" and a basic element of the diet, one that inspired cooks to concoct recipes for publication and diffusion.

So, speaking of pasta, and looking at the pasta that we are used to eat today, is important to sketch out the history of the tomato up to their meeting.

The tomato reached Italy, officially at least, in the 17th century. It was brought into the country by the Spanish but they did not at the same time introduce any culinary preparations in which the fruit was employed.

It apparently required more than a century and the ingenuity of the Southerners, stimulated by chronic famine, to bring the tomato and pasta together. ù

Who took that fateful step, it is impossible to say but it appears that some teamsters in the Trapani area, who were soon emulated by the rural inhabitants of western Sicily, started the practice of adding a substantial amount of tomato cut into slices to the water in which macaroni or vermicelli was boiled.

In Campania, the adopted homeland of pummarola or tomato sauce, cultivation of tomatoes on a large scale was late in getting under way, despite the fact that the plant was first grown in the region as early as 1596.

What is certain is that a dish of macaroni flavored with a bit of cheese was selling at the end of

the 18th century for two centesimi (cents) in the inns of Naples. In the North, meanwhile, tomatoes were cultivated as ornamental plants.

The Sienese botanist Pietro Andrea Mattioli (1500-1570) was the first in Italy to call the tomato by the name it has since retained in Italian, pomo d'oro or golden apple. Mattioli was referring to one of the colors the tomato assumes during its ripening.

While Italians refer to the fruit as a pomodoro (the plural is pomodori), the French, English, Spanish and Germans continue to use terms directly derived from the name the Nahuatl Indians of Mexico gave it, tomatl..

In discussing the eggplant, Mattioli reported in 1544 that "another species, known as Pomi d'Oro, has been brought into Italy in our day. The fruits are compressed in shape, like rose apples, and grow in clusters. At first they are green in color and from some plants are as red as blood when they ripen, while others are the color of gold. Both are eaten in the same way." That "way" was boiled, cut in slices, dredged in flour and fried.

Within three centuries, the tomato had been accepted everywhere in Italy. In Il Cuoco Galante ("The Gallant Cook"), one of the first complete Italian cookbooks, Neapolitan Vincenzo Corrado (1734-1836) wrote that

"various tasty dishes can be made from the tomato. Sauce prepared from them can be used to flavor meats, fish, eggs, pastas and vegetables.

A good cook can easily create delicious tidbits from them and a universal sauce [since it can

be used in numerous ways]. The tomato not only pleases the palate with its flavor but also benefits the body, since its acidic juice aids digestion, particularly during the summer season when

people's stomachs are flaccid and prey to nausea because of the overpowering heat.

These summer tomatoes are round and of a saffron color. They have a skin that must be removed by rotating them over the coals and plunging them afterward in boiling water. It is possible to remove the seeds, to assure more delicate and satisfying preparations, by opening a hole at the point where the stem joins the tomato or cutting the tomatoes in half."

Earlier, however, the literature of the tomato was rather scanty, which is the most convincing evidence that the plant was not widely diffused.

One of the first publications dedicated to the cultivation of tomatoes was Giovanni Francesco Angelita Roco's I Pomi d'Oro, issued at Recanati in the Marches in 1607. However, it was not widely circulated.

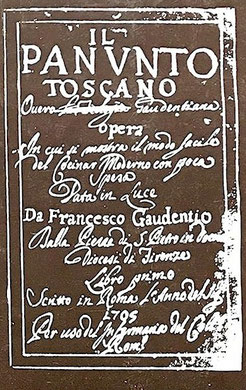

A century later, in 1705, Francesco Gaudentio, lay coadjutor for provisions of a community of

Jesuits in Rome, provided the first Italian recipe for cooked tomatoes in his Panunto Toscano, the manuscript of which is preserved in the Communal Library of Arezzo. The recipe:

"These fruits are very similar to apples. They are cultivated in gardens and are cooked in the following way: pick the tomatoes, cut them in pieces and put the pieces in a pan with oil, salt,

chopped garlic and wild mint. Stew them, frequently stirring the mixture.he dish will be even better if you add a bit of tender molignane [eggplant] or white cucuzze [squash]."

Only in the late 18th and early 19th centuries was the tomato "officially" endorsed by gourmets and leading chefs, beginning precisely with Corrado, a Celestinian monk who, from his privileged observation post in Naples, reported that he had tasted his first "leg of kid coated with tomato paste and larded with lardoons and spikes of rosemary and roasted in the oven with butter and herbs."

In the third edition of Il Cuoco Galante, published in 1773, the attentive gourmet listed the following recipes involving tomatoes: (from Treatise One - Pythagorean Fare) stuffed with veal, dressed with salpicanti (saupiquet, a pungent sauce), stuffed and cooked in butter, filled with greens, stuffed with rice, alla Corradina, stuffed with fish, cooked in truffle sauce, alla napolitana, in croquettes, in fritters and in a pudding.

Two years later, Francesco Leonardi, former cook to Catherine II the Great, Empress of All the Russias, published his Apicio Moderno. In the second edition of that work (1797), there is the first recipe for cul“ (or coulis), a tomato sauce in the French style that was then highly fashionable. However, there is no mention of its possible use with pasta. A further 40 years were to pass before the first recipe for vermicelli col pomodoro (fine spaghetti with tomato) appeared.

However, it is always possible that many housewives had already been combining tomato and pasta for some time, although such a practice was not widely diffused at the time.

The fascinating Neapolitan watercolors of the early 19th century always depict maccaronari or macaroni eaters stuffing themselves, using their hands in the process, with pasta in bianco.

That means it was flavored only with grated cheese - or incaciata, according to the expression of that period.

The first historical vermicelli co le pommodoro was described in 1839 by Ippolito Cavalcanti, Duke of Buonvicino (1787-1860), in "Cucina Casareccia in Dialetto Napoletano" ("Home Cooking in Neapolitan Dialect"), an appendix of La Cucina Teorico-Pratica (Theoretical and Practical Cooking).

In Rule 10 of the chapter devoted to sauces, Cavalcanti adds:

"It [tomato] is good if you want to prepare macaroni or any other type of small pasta. You should not put the sauce on top of boiled meat, eggs, chicken and fish, which are good with a bit of butter. Make this excellent sauce to flavor vermicelli but, if you baste it with oil, it will be even better and more savory."

It is in only in the first half of the 19th century that the consumption of dried pasta rapidly spread throughout society, became fashionable and serving it was a mark of distinction.

THANKS TO THE FORK!

However, the addition of sauce made pasta a messy dish to eat with the hands and an instrument that was as curious as it had been neglected until that time, soon began to appear on the tables of the middle class: the fork.

That implement had been around in various forms for several centuries and had filled various functions at the tables of refined and snobbish households throughout Europe.

However, its use as a standard utensil had not been established. The fork was put out on the tables of a restricted number of nobles in order to impress guests rather than assist them in eating.

The spread of the practice of eating pasta dressed with tomato sauce led to the adoption of the fork as an everyday utensil.

The numerous models previously known were abandoned. The shape and proportions of the fork were modified and, within a few years, a single format appeared. The new standard implement had four curved tines, the length of which was no more than twice their combined width.

Any maitre d'hotel today could deliver a lengthy commentary on the precise shapes and functions of forks, including those used for eating fish, meats, "sauced" dishes, desserts and fruits.

And he would no doubt express disapproval of any misuse of the utensil. It is a fact, however, that for two centuries now it has been the practice in private homes and most restaurants throughout the world to use for nearly all purposes only the fork designed for pasta, with its four curved tines.

Pasta flavored with oil and tomato constitutes only a beginning, not a gastronomic finish line, for that essential dish opened up a new world of flavors and aromas.

While inventiveness was stalled for centuries at boiled vermicelli with, perhaps, some cheese added to make it more tasty, the imaginations of housewives, initially, and then of chefs and gourmets yielded within the space of a few years a host of preparations in which the finest products of the Italian tradition, like mozzarella, provola cheese, Parmigiano, ham, guanciale (cured pork cheek) and an unending parade of cheeses, fish, meats, preserved foods and delicacies were twinned with tomato and the sauce made from it.

Pasta and all these traditional products were called into play in a veritable orgy of innovation, in which Italian cuisine was entirely renewed.

The 19th century, the century of great political changes in Italy, from foreign domination to the national unity, the century of Risorgimento, Giuseppe Garibaldi and Cavour, is also the time of the final evolution of pasta, the passage from misery to nobleness, from a provision to a delicacy.

And in the same moment in which the creativity of the chefs breaks-out, the inventive power of pasta producers emerges.

In this century, small and big pasta factories start methodical research for new shapes able, at

the same time, to catch the attention of the consumers, and assure them new and unknown gastronomical pleasures.

The history of pasta in the last two centuries is a mix of fantasy, technology and marketing: a long and complex story to be continued soon...

GO TO:

RuvidaMente

RuvidaMente